NEPAL: The Kumari Caves

by Rob FreyChapter 1: Introduction

While working for an unnamed military, I heard the story of the Kumari Caves, a cave system in central Nepal that supposedly drives you mad if you enter it. Beyond that, all I had were rumors and hints of villages that might have someone who might know where the caves might be.

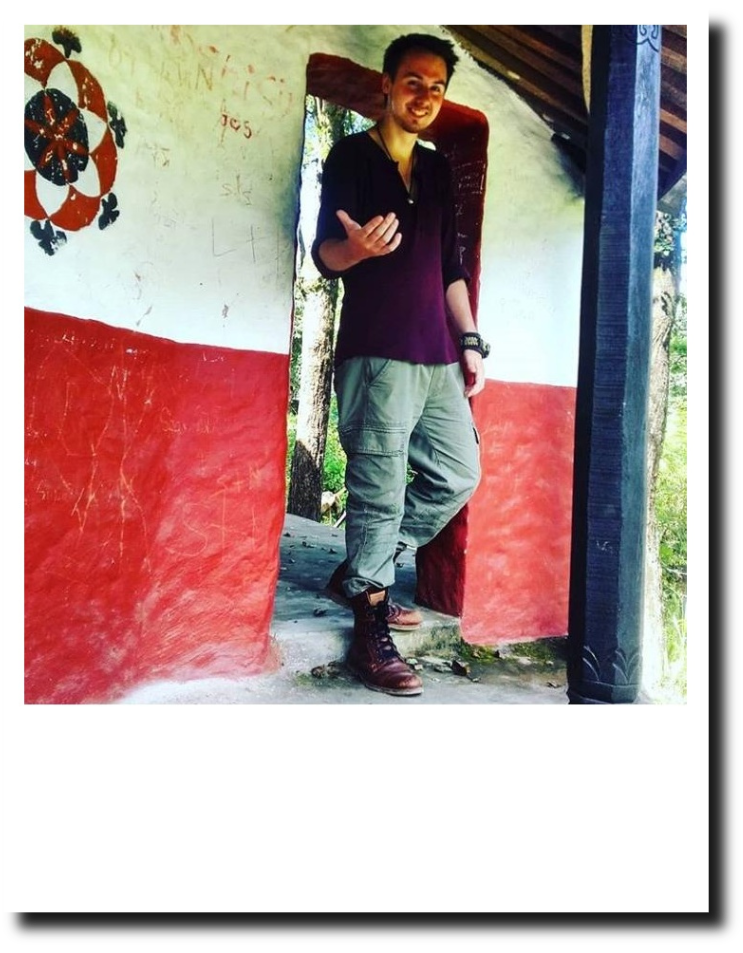

So: caves that drive you mad, no clear destination, in a foreign country? Obviously, I was going. I hired my buddy Zeebo, a Pokhara local, as a guide. Together we began preparing for the expedition: provisions, machete, snakebite kit, first aid, tents, you know, all the fun toys.

While we were getting ready, Zeebo mentioned that his grandma, who lives roughly in the direction we were heading, knew all the old local stories. So that became our first destination.

Chapter 2: Jungles and snakes, snakes and jungles

We packed up our flat wich was just a roof held up by wooden beam with no walls, built on top of a building, and said our goodbyes to our friends in Pokhara. As is customary, we each received a scarf tied around our necks for the journey. It also happened to be the Day of Friendship, so we got matching bracelets as well. I felt like the belle of the ball, all bedazzled like that.

It was an incredibly hot and humid day. We had to cross half of Phewa Lake by boat to reach the hiking path that would lead us to our first campsite. We chartered a little motorboat with a captain who was clearly jealous of my scarves and bracelets. We crossed the lake, passed the island with the temple, and hit land. That was the moment we entered the jungle for the first time on this expedition.

For those who’ve never been in a jungle, here’s a quick description: it’s hot, and so humid it feels like breathing water. It’s loud—animals scream, grunt, hoot, screech, fart, and possibly email each other. Everything moves, but somehow it all feels still. Greens and browns in endless variety. And nearly everything you see has the potential to hurt or kill you—or both, in an order of its own choosing.

It’s overwhelming yet calming… like the smell of French fries after a night out.

So there I was, in the jungle. Not for the first time, but for the first time without a bunch of trained professionals keeping me alive. Just me and a standard-issue Zeebo, who assured me he knew exactly how to get us from point A to point B safely.

We hiked for a few hours, took breaks, soaked in the constantly changing scenery. Nearing our first campsite, we came upon a wide, straight path—wide enough for a car—and saw something up ahead. At first, it looked like a black stick about the length of my leg and as thick as my wrist. (Remind me to stop using my own body as a measuring system.)

As we got closer—about eight feet or two meters—I realized it was a snake. Completely black, and judging by the shape of its head, venomous.

First thought: Crap.

Second thought: Right, I have Zeebo. He’ll know what to do.

So I stop Zeebo and say, “Oi—snake.”

Next thing I know, I’ve got a tiny Nepali fellow balancing on my right shoulder, screaming “SNAKE!!” in total panic.

That’s when I learned two things:

1. Apparently, I was in charge of safety.

2. I could balance a human on my shoulder.

I gave the snake a wide berth while Zeebo, still shrieking, remained perched on me. Once we were at a distance Zeebo deemed “safe,” he jumped down, high-fived me, and declared we handled it perfectly.

Yeah. Sure, little buddy. Great job.

We reached our campsite, a basic shepherd’s shelter. Zeebo made a fire, cooked an amazing dinner, set up our sleeping bags, and even sang while working. Meanwhile, I had only managed to take my backpack off. So Snakes aren’t Zeebos strong suit but everything else you might need on an Expedition, he nailed it.

Chapter 3: Finally, a Clue!

After a short and uncomfortable night, we resumed our journey. Two uneventful days later, we arrived at the village.

As soon as the kids spotted Zeebo, the celebrations kicked off. We were dragged to the village center. I bowed left and right in greeting while people poured into the square—uncles, aunts, nieces, nephews, Zeebo’s parents, and all his sisters. The whole village had come out to celebrate his return.

At that point, I found myself wondering: was Zeebo really that loved? Or had his snake-handling skills just been missed?

Tables were brought out, fires were lit, and the smell of incredible food drifted from every home. While Zeebo was whisked away to his family’s hut, my anti-social arse was left in the middle of the crowd.

I tried to help with the preparations, but that only earned me looks of heartbreak. Apparently offering help as a guest is an insult. So I kept busy by checking my gear, taking inventory, writing in my journal, and pulling my best “deep-in-thought explorer” face.

Eventually, Zeebo came back to fetch me and introduce me to his family. They were all lovely—except one of his sisters.

And I say this with the utmost respect for Zeebo and his family:

She looked like Jabba the Hutt, smiled like Gollum, and had the personality of a starving grizzly bear.

She stared at me like I was a steak, and sadly, she’d become a problem later.

At dinner, Zeebo introduced me to his grandma, who looked like she was a couple hundred years old. We didn’t speak the same language, and she didn’t hear well—but based on the awkward silences and nervous laughs around her, she seemed to enjoy ending sentences with wildly inappropriate jokes. I liked her.

With Zeebo translating, Grandma told me about how she once lived in a village called Armala—not far from Pokhara—and how, as a youth, she ventured into the Kumari Caves on a dare. Apparently, it was common among the young folks in Armala back then.

That was it. A real clue. A solid lead to what had, until then, only been a legend. I asked for more details, but Zeebo couldn’t keep up with the translation and Grandma got distracted by the food.

My questions would have to wait.

I was seated between Zeebo’s youngest sister and his Blob sister. The food was amazing, the mood was festive, and I got to chat with folks who spoke some English. I even picked up a few useful survival tips from Zeebo’s uncles and father.

But the menace of the Blob Sister loomed—literally—over me.

At one point, she grabbed my arm with a grip strong enough to pin an elephant. Then she leaned in and grunted in my face with a breath that smelled like rotting death, curry, moldy fish, and more rotting death. My eyes watered. I swear half my eyebrows burned off.

A tipsy Zeebo leaned over and said, “She asked if you’re married.”

My survival instincts kicked in hard.

“I have an incredibly beautiful and supportive fiancée at home,” I blurted out.

Total lie. We all knew it, I knew it, Zeebo knew it, Grandma knew it, and worst of all, Jabba knew it.

She grunted again. Zeebo, trying not to laugh, translated: “She says she doesn’t believe you… and that you should marry her.”

She flashed me her eight (maybe nine?) yellow teeth and grinned at Zeebo, who gave me an apologetic shrug.

That’s when it hit me: Zeebo set me up.

He threw me in front of the sister-shaped bus.

I gave him a look that said, You’re dead, mate.

He looked away, ashamed.

Her grip tightened. I panicked.

Quickly, I grabbed a steaming cup of Nepali butter tea, pretended to take a sip… and “accidentally” spilled it on her arm.

She yowled. I bolted, muttering something about getting a towel, and fled to the hut where my sleeping bag was. Safe… for now. But just in case i moved my stuff to another Hut

That night, I heard something the size of a chubby bear rummaging through the hut I’d originally been assigned. Then came a howl so loud it must’ve scared every tiger in the jungle.

Jabba wouldn’t give up easily.

At 6 a.m., I packed my gear, crept into Zeebo’s sleeping spot, and gently placed a hand over his mouth. I savored his panicked expression for a moment before whispering, “We’re leaving. Now.”

He didn’t argue. Packed quickly, grabbed some extra supplies, avoided eye contact. He felt bad—I could tell. He said goodbye to his folks and promised to return soon.

And just like that, we were off to find the way to Armala.

Chapter 4 – We Made It… Or Not?

Zeebo was incredibly attentive and hard-working over the next few days as we trekked through the jungle towards Armala, located east of Pokhara. He still felt guilty about earlier events, but I told him not to worry. Soon enough, we were back to our usual banter.

After a few days, we reached the outskirts of Pokhara again. At one of the first villages we passed, Zeebo asked some locals if they knew where Armala was. They gave us the coordinates, and Zeebo, ever the pro, quickly checked the GPS and marked down our new target.

As the rice terraces of Armala came into view, a wave of excitement rushed through me. Apparently, I picked up my pace without noticing, because I could hear Zeebo panting beside me. About 2.5 kilometers from the village, at a bridge, we encountered a young man roughly our age. He said every vehicle that passed had to pay a toll—and insisted we pay as well. It had been a while since I last saw a mirror, but I was fairly confident I didn’t resemble a car. It took Zeebo a while to convince the guy we weren’t motorized, and eventually, he agreed to guide us into the village. Finally!

As we arrived, the young man shouted something to two boys sitting in front of a small shop. Those two boys later became very important to my Expedition. They darted off toward the village center. Our guide stopped now and then to chat with locals, but we eventually made it to the central square. A small crowd gathered, many pulling out ancient-looking phones to snap a photo of the weird white guy in their midst.

Then, the village elder—or at least the guy in charge—emerged from a nearby house with the two boys in tow. He greeted us and had a brief, fast-paced conversation with Zeebo. Zeebo translated: the elder's name was Tenzin, and he welcomed us to Armala. I asked Zeebo to express our gratitude and to explain why we were there.

After the explanation, murmurs rippled through the villagers. Tenzin responded quickly, gesturing wildly, pointing south and at the boys. He bowed to us, and we bowed back—even though I had no idea what was going on. Then he returned to his home, and the two boys stood in front of us, grinning from ear to ear. They had a brief conversation with Zeebo, became even more giddy, and then ran off again.

I turned to Zeebo. “Well, what was that all about?”

Zeebo explained: Tenzin had asked to see our permit for documenting the Kumari Caves.

Permit? Permit?! Damn. I hadn't even thought of that.

Suddenly, I had very mixed feelings. On one hand, we needed an official permit to legally explore and document the caves. Bureaucracy—ugh. But on the other hand… Tenzin asking for a permit meant the Kumari Caves were real—and close!

Zeebo said he'd already explained everything to Tenzin and arranged for us to get the permit. We’d be guided by two locals… the very two boys we'd just met.

A few moments later, the boys returned with small backpacks and huge grins. They introduced themselves in English. The older one, around 15, was called Pretam, and the younger, 13, was Nabin. They told us we needed to obtain the permit from a priest who lived in a cave a few days south of Armala. Turns out, to document a religious site and study potential artifacts in Nepal, you need the approval of the local religious leader. In our case, a cave-dwelling priest.

Chapter 5 – A Priest That Lacks Enthusiasm

So, I had two new expedition members, a new goal, and all the motivation in the world. We stocked up on supplies, and I promised my three guides vast riches and… traditional German Christmas songs. Don’t ask—it was one of Pretam and Nabin’s conditions for leading us to the priest. They had flutes. They had drums. And they were not afraid to use them… at all times. At. All. Times.

So, off we went—me and my merry band of wannabe Beatles. It was a grueling few days to the priest’s cave, but the boys were in high spirits, always laughing, singing, playing their instruments, and soaking up Zeebo’s knowledge. They saw him as a big brother, and he took the role seriously. Turns out, Zeebo had initially convinced them to be our guides in exchange for a bag of chocolate. I later insisted we give them proper payment to help with school expenses—they earned it.

Our provisions were tight, but we hoped to resupply in a village along the way. One morning, about a day from our destination, the boys revealed a surprise—honey!

I love honey.

We made some flatbread over the fire, brewed some butter tea, and when I saw that golden nectar, I offered to trade some of my dried fruit for extra helpings. The boys looked confused but agreed. I slathered 4–5 spoonfuls of honey on my bread. Their shocked expressions didn’t register until it was too late.

Apparently, it was mad honey. Wild honey from the high altitudes of Nepal, with psychoactive properties.

One teaspoon = high for half a day.

I had five.

I barely remember the rest of that day. I was told I giggled for hours in my sleeping bag, wandered off into the jungle claiming I needed to pee, vanished for three hours, and returned to announce… I still needed to pee.

That day, we didn’t travel. And the boys stripped me of all honey privileges.

The next morning, I woke up still a bit woozy. I was told what had happened, and I couldn’t even be mad. It was kind of hilarious. We resumed our journey, and a few hours later, we reached the priest’s cave.

It was about 500 meters deep, with narrow passages that forced me to crawl, jump, and climb. Honestly, I felt like a proper adventurer in there.

At the far end, in a humid, flower-laden chamber filled with offerings, stood the man himself—the most uninterested human being I’ve ever encountered. Imagine a cave-dwelling priest, surrounded by bats, occasionally getting visitors with gifts. You’d think that might brighten his day, right?

Wrong.

Meet Angus the Unenthusiastic, my nickname for him.

My guides explained our mission. Angus responded with a sigh, rolled his eyes, and held out his hand. I assumed he was channeling some emo phase energy, but it turns out he was asking for… money.

That’s right. A bribe. For a blessing.

I couldn’t believe it, but I needed that blessing. So I paid the moldy bugger.

He sluggishly mixed a bright red paste that smelled like fire and disappointment, flung a flower necklace at me like it had wronged him personally, muttered something, and slapped the red goop onto my forehead.

Did I mention his face looked as punchable as his attitude?

Anyway, the deed was done.

On the way back, that red dot on my forehead itched like hell—but I couldn’t scratch it while climbing and crawling.

Back outside, I asked if I could wipe it off. The boys looked horrified. Turns out, Tenzin needed to see that dot. Proof of blessing.

And so began a full week of jungle trekking—with an itch on my face from hell’s itchiest doormat.

Let’s just say I was the definition of sunshine on the way back.

Chapter 6 – Now I Am an Explorer

By the third day on the way back to Armala, provisions were low—and so was morale. We all snapped now and then, needed more breaks, and the jungle started to wear us down.

Enter our savior.

That afternoon, as we set up camp and did our usual snake-and-creepy-crawly sweep, Nabin found a massive snake near the edge of our site. We kept our distance, carefully watching its every move. Even Zeebo held his ground—impressive, considering his earlier fear of snakes.

It had the classic traits of a venomous snake: wedge-shaped head, slit eyes, and dark, intimidating skin. It was thick, long, and—importantly—food.

I grabbed the machete, found the right angle, and with one clean strike, decapitated the snake. The body thrashed violently for what felt like forever. I carefully moved the head with the blade, avoiding contact, and the boys started preparing the fire. Zeebo set up the rest of camp while I, using the skills his uncles had taught me, skinned, gutted, and prepared the snake.

I burned the head over the fire to destroy any lingering venom, then buried it deep away from camp.

We roasted the meat with what salt and pepper we had left—and that night, we feasted. Like kings.

For once, I didn’t even mind the musical instruments.

After weeks in the Jungle my Clothes begun to reek, so when we arrived in Armala the next day i was beyond happy. Pretam and Nabin were greeted with the same warmth and celebration that Zeebo had received at his village. Tenzin inspected the strange mark on my forehead, spoke intensely with Pretam and Nabin for a while, and finally declared with a satisfied grin that we were worthy to enter the caves.

That evening, the four of us feasted like kings. My guides laughed, drank tea, and celebrated, while I sat in tense silence, unable to join them. Tomorrow was the day everything in my life would change. I barely slept.

At dawn, I was as ready as I’d ever be.

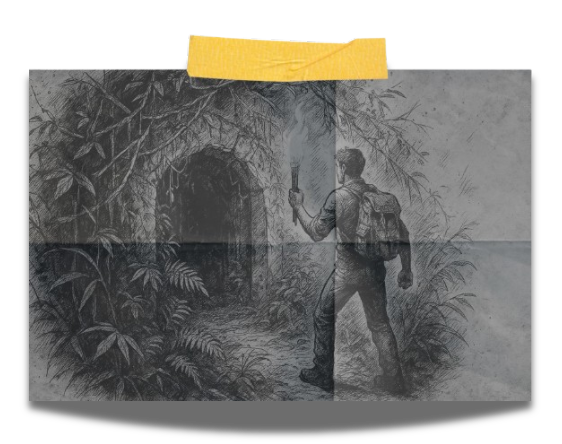

With grim determination, I followed Pretam and Nabin into the jungle. The Kumari Caves were just outside the village. We hacked through thick vegetation with machetes, pausing only once—when Nabin had to stop to peel leeches off his bare feet. He stubbornly refused to wear anything but sandals, no matter how much we teased him about it.

Eventually, we reached a small hill. Pretam slashed through the last vines, and there it was: the entrance to the Kumari Caves. Two stone pillars stood on either side of a triangular roof set into a rocky wall. To my surprise, the words “Kumari Caves” had been scratched into one of the pillars in English, using Latin script.

Pretam explained this was done generations ago to frighten off British soldiers during the occupation of the region. It worked.

I took a photo of the entrance, then stepped closer. Five uneven stone steps descended into the darkness. We turned on our flashlights and entered.

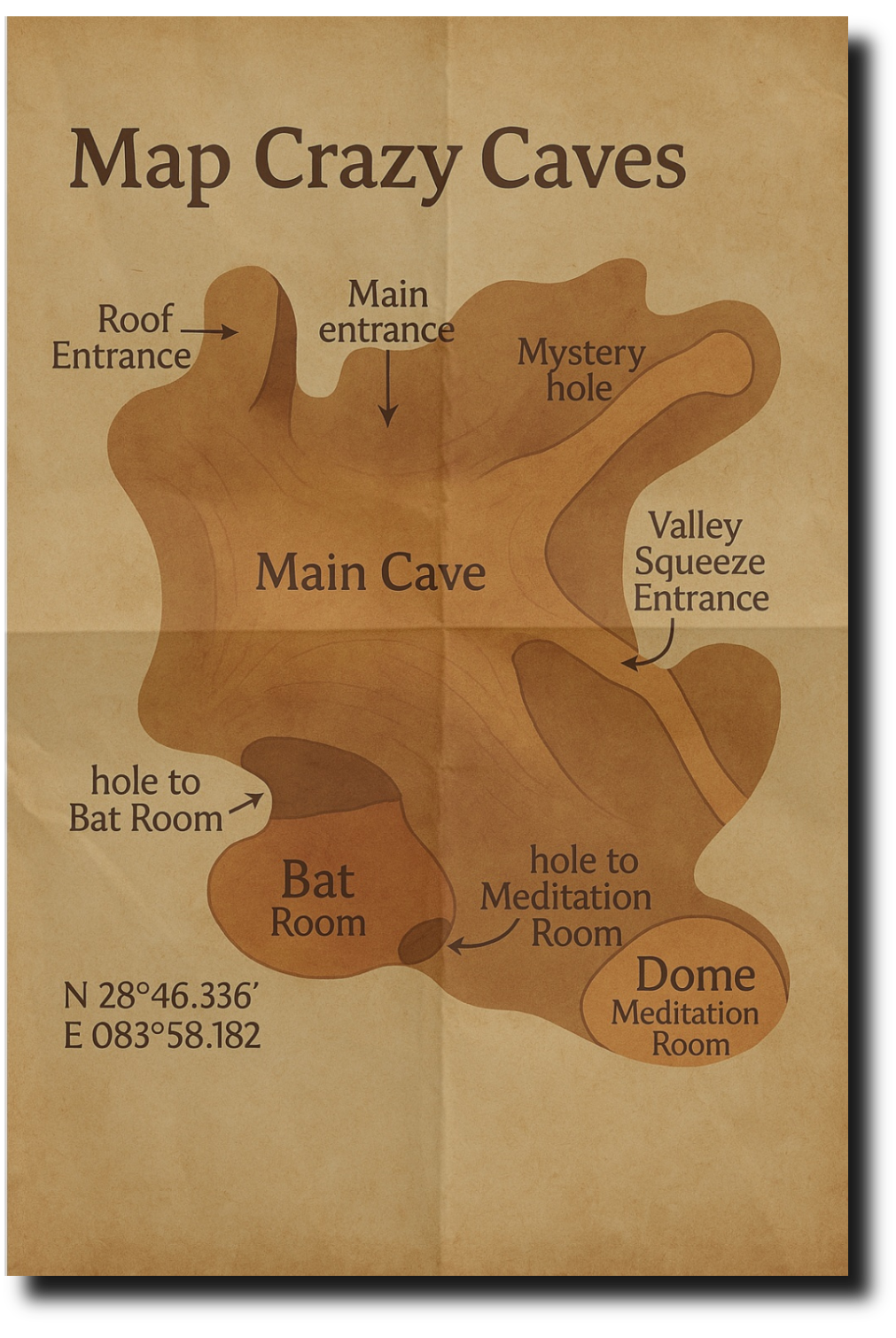

The main chamber stretched roughly 300 meters long and reached 15 meters high at its peak. There were three entrances: the main one we used, a large northern entrance that had been almost entirely sealed up, and a third high up in the southwestern ceiling—likely a natural vertical shaft. The walls were encrusted with crystals, so when we moved our lights, dazzling reflections danced across the chamber.

A few bats fluttered overhead. We noticed they all seemed to exit through a small hole in the eastern wall—about a meter wide and a meter high. We could all crawl through it. I went first, sliding my backpack ahead of me. The tunnel was low and narrow, half-filled with cold water thick with bat guano.

On the other side, we entered a chamber roughly 20 by 20 meters wide, with a ceiling that soared nearly 30 meters high. Hundreds of bats flapped in frantic circles overhead, brushing against us as they flew. But nothing could stop us now.

At the far end of the bat chamber was another tunnel. This one was tighter and longer. We crawled for nearly ten minutes before emerging in a third, final chamber.

This space was small—only about 10 meters by 5, and 4 meters high, with a natural domed ceiling. In the northwest corner stood an altar, sculpted over untold centuries from stalagmites. The rock had been smoothed down, shaped into a table-like form. Atop it lay several candles and a treasure trove of artifacts: coins from multiple time periods, amulets, tiny bronze boxes, Hindu and Buddhist statues, a few slimy scraps of parchment, and—at the very center—a Phurba ritual dagger.

I picked up the Phurba.

That was the moment I became an explorer. No going back from there. I had found my first piece of missing history.

The story that the caves make you mad was also quickly solved. The cave had three entrances so the wind always whispers through, the crystals in the stone walls reflect shapes, bats always circle you and mixed with local legends, we have: a cave that turn you crazy.

The treasure was discovered, the legend solved—now the real work began. We took photos and videos, sketched the cave layout, made measurements, and carefully packed the artifacts into bags. We documented as much as I knew how to back then, and then we made our way back to Armala.

A few days later, I stood in the Chitawan History Museum, shaking hands with the museum director. He accepted most of the artifacts so students from Nepal—and beyond—could study them. Some pieces I was allowed to keep for personal study and to lend out to universities. It felt like the right thing to do.

I had lived in Nepal for half a year by then. It was time to move on.

As I packed my bags to head for the airport, Zeebo came into my room. He’d heard I was leaving and came to say goodbye. Maybe we shed a few manly tears, no shame in that. We reminisced about our adventures, and then he asked what was next for me.

He told me he was applying to join the army. Then he looked at me and asked,

“So what’s next for the explorer Rob Frey?”

I grinned and said,

“What do you know about the pirates of Nassau?”

-Rob Frey

-

Photos unless otherwise stated are © Areas Grey Ltd. Unauthorized use is prohibited.

Historical Paintings from:

https://public.work/

Written by

Rob Frey