LEGEND: THE BUZZARD’S TREASURE

By Adam ‘Grey’ CochraneOverview

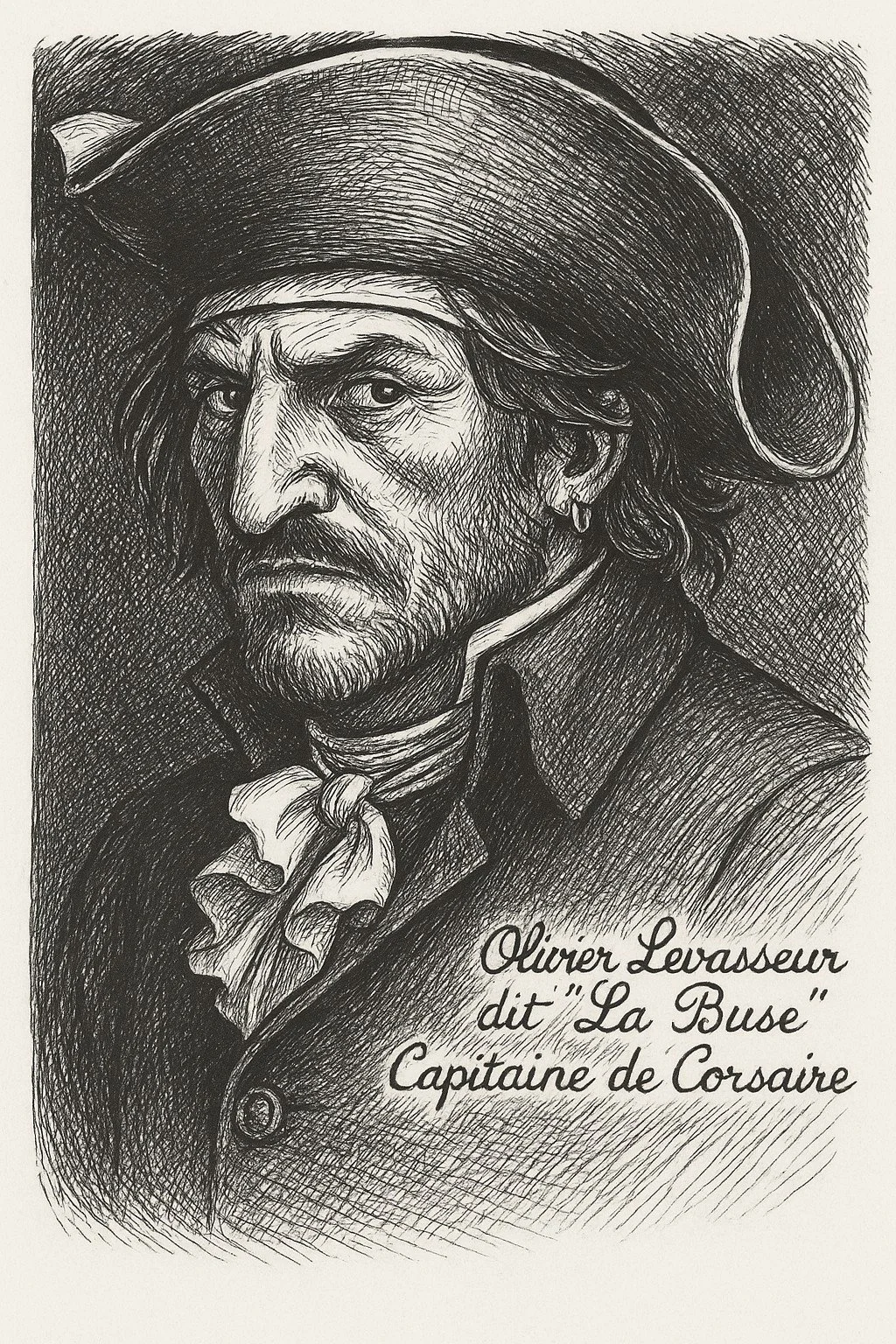

Olivier Levasseur was a French pirate between 1688 and 1730. Nicknamed La Buse (The Buzzard), he is known for allegedly hiding one of the biggest treasures in pirate history, estimated at over £1 billion, and leaving a cryptogram behind with clues to its whereabouts.

Over the years since the cryptogram was released into the public domain many treasure hunters have gone in search of La Buse’s treasure in hopes of striking it rich, but despite these attempts, nobody has yet recovered the unimaginable treasure believed to have been hidden by the pirate.

THE LEGEND

Levasseur was born in Calais, France sometime during the Nine Years’ War (1688 – 1697). During the War of Spanish Succession (1701 – 1714) he procured a letter of marque from King Louis XIV becoming a privateer for the French crown. Instead of returning home at the end of the war he joined the Benjamin Hornigold pirate company in 1716.

One year later the Hornigold party split and Levasseur partnered with Samuel Bellamy and was elected captain of William Moody’s crew in 1718 operating together with Howell Davis and Thomas Cocklyn.

From 1720 to 1724 Levasseur joined forces with John Taylor, Jasper Seagar, and Edward England with Paulsgrave Williams as quartermaster. They launched raids from a base on the island of Sainte-Marie, off the coast of Madagascar. After raiding Laccadines they sold the loot to Dutch traders for £75,000 before marooning England on Mauritius.

The remaining crew later captured the Portuguese great galleon ‘Nossa Senhora do Cabo’ (Our Lady of the Cape) or ‘Virgem do Cabo’ loaded with treasures consisting of bars of gold and silver, dozens of boxes of golden Guineas, diamonds, pearls, silk, art, and religious objects including the Flaming Cross of Goa.

THE TREASURE

Each pirate received £50,000 worth of golden Guineas as well as 42 diamonds with Levasseur taking the Flaming Cross before retiring from piracy and settling down in secret in the Seychelles. In 1730 Levasseur was captured near Fort Dauphin, Madagascar.

Before Levasseur was hanged at Saint Denis, Reunion island in 1730 he wore a necklace which he threw to the crowd exclaiming “Find my treasure, the one who may understand it”. While the necklace has since been lost the 17 lines of a cryptogram that was contained within the necklace continues to puzzle treasure hunters today.

The Flaming cross of Goa is described as being seven feet tall, encrusted with diamonds, rubies and emeralds. It was so heavy that three men were needed to carry it!

THE CLUES

The cryptogram first appeared in a book called “Le Flibustier Mysterieux” which was published in Paris in 1934. It had been written by a man named Charles Bourrel de la Roncière. Charels was a renowned and respected French historian and librarian whose works marked the revival of naval history studies.

The cypher as seen here, consists of 17 lines of symbols which at first glance would appear to be nonsense. However, Roncière correctly identified the symbols as being what is known as a “pigpen cipher” also known or referred to as the masonic cipher, Freemason’s cipher, Napolean cipher, and tic-tac-toe cipher.

The cipher uses a simple substitution cipher, letters of the alphabet are placed into four grids. Each part of the grid can then be used as a symbol in exchange for that letter in the secret message. The 4 grids of letters are then used as a key to break the coded message.

The pig-pen cipher is an ancient one, it can be traced back to the Knights Templar during the crusades. Fortunately for treasure hunters this type of cipher is very easy to break without the key which is exactly what Roncière did. Exchanging the symbols for letters he was able to decipher the cryptic texts. However, what it revealed was not expected.

CONCLUSION

The decrypted text below which was revealed after Roncière broke the cipher surprisingly doesn’t reveal anything to do with piracy or treasure, in fact it would appear more like a recipe of some sort:

1. aprè jmez une paire de pijon tiresket

2. 2 doeurs sqeseaj tête cheral funekort

3. filttinshientecu prenez une cullière

4. de mielle ef ovtre fous en faites une ongat

5. mettez sur ke patai de la pertotitousn

6. vpulezolvs prenez 2 let cassé sur le che

7. min il faut qoe ut toit a noitie couue

8. povr en pecger une femme dhrengt vous n ave

9. eua vous serer la dobaucfea et pour ve

10. ngraai et por epingle oueiuileturlor

11. eiljn our la ire piter un chien tupqun

12. lenen de la mer de bien tecjeet sur ru

13. nvovl en quilnise iudf kuue femm rq

14. i veut se faire dun hmetsedete s/u dre

15. dans duui ooun dormir un homm r

16. esscfvmm / pl faut n rendre udlq

17. u un diffur qecieefurtetlesl

At this point, any sensible person would look at this and regret wasting their time decrypting it in the first place. So why did a well-respected historian like Roncière after discovering the decoded message to reveal nothing and with apparently no evidence to link the text to any pirate or treasure would he then proceed to risk his reputation and write a book about it?

This is the real reason why this legend lives on today and why it has led so many treasure hunters since 1934 to go in search of the lost treasure of Olivier Le Vasseur, some spending their entire lives and spending every bit of their fortunes looking for it.

What do you believe?

-

All photos unless otherwise stated are © Areas Grey Ltd. Unauthorized use is prohibited.

The La Buse Cypher - Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Crypto_de_la_buse.jpg